In a letter to his brothers in 1817, John Keats wrote that the quality that defines a “Man of Achievement” is that he is ‘capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’ – a state of mind he summed up as “Negative Capability”.

In a world that feels increasingly multi-faceted, fractured and fast-paced, the notion any sort of objective ‘fact and reason’ feels more and more like wishful thinking from simpler times, as we’re faced with ever-evolving news cycles, noise and (mis)information.

Because modern life is defined by complexity. We are constantly having to sift through headlines, hot takes and hysteria. But just as our lives have got nosier, so too has our need to find instant gratification and immediate answers amongst the clutter.

It sounds like a contradiction – in some ways it is – but it rings a bell, right? There’s a kernel of truth to the idea that personally, professionally and societally we’re all looking for a quick fix. Yet easy answers are hard to come by, if they even exist at all anymore.

And this is why Keats’s negative capability has such a profoundly strong impact on our jobs as strategists.

In a world addicted to simplicity and speed, strategy needs the discipline to hold the contradictions of modern life long enough for richer insights to form. In short, strategy needs to be negatively capable if it’s going to deliver the most positive outcomes.

Less KPIs, more Keats

Great brand strategy thrives on ambiguity. A brand or business never has one fixed “truth” – it’s a negotiated space of meanings between company, culture, and consumer, with a number of competing perspectives to navigate.

The pressure for business leaders and clients in brand work is often to “nail the proposition”. When faced with too many deadlines and the unrelenting pace of culture, insights and research teams can often feel like they need to deliver clarity and solutions as soon as possible. There is always the fear that the problem will morph, the conversation will move on, and we will fall behind the pace of change.

But if you rush, you risk shrinking your insights into something flat and one-dimensional. The negatively capable strategist waits, collects inputs, identifies and navigates tensions, and allows competing narratives to jostle until something richer crystallises.

Instead of striving to collapse multiple meanings into a single “essence,” our job as consultants and strategists is to embrace the nuances to cut through the noise. Negative capability privileges openness to what doesn’t yet fit. That’s crucial for spotting the nascent cultural shifts, or contradictory consumer desires that could hold within them the sharpest insights and strongest solutions.

The cultural environment we work in is accelerating. When signals multiply and contradict each other, the temptation is to compress them into a neat insight. Put it in a sentence. Make it pithy. Make it sing.

But let’s not confuse simplicity with clarity. All too often all this does is collapse insights into simplistic clichés (“authenticity,” “community,” “empowerment”) that no longer differentiate brands.

Negative capability gives a principled way to resist that compression. It says that the real value is in sitting with contradictory ideas – treating dissonance not as something to resolve, but as inspiration. That patience creates space for fresher, more resonant strategic leaps.

Switch off to switch on

Fittingly for an idea that prioritises ambiguity over certainty, negative capability has been reinterpreted time and again over the last 200 years. It’s most obviously been analysed through the prism of literary criticism, but has also been applied to psychoanalysis, Buddhism, and has even turned up in an episode of True Detective.

What this speaks to is that negative capability is flexible, accommodating, even chameleonic. Yes, it is about holding multiple perspectives in mind without trying to collapse them into an easy answer. But it also expresses something a little more grounded too – the ability to take a step back. To stop reaching or chasing after answers. To just give your mind space to think.

It goes without saying that to create great strategy – or great thinking in general – we need the time and space to create the conditions where ideas can develop, and where tensions can be held in place.

To bring Keats into a more medical context (he was medically trained after all!), negative capability comes to life in the parasympathetic nervous system – the body’s “rest-and-digest” mode – which creates the conditions for imagination.

When our parasympathetic nervous system takes the lead, our heart rate and arousal drop, and our cognitive control loosens. In that calmer state, the mind more easily wanders and incubates problems – stepping away lets competing ideas jostle unconsciously and recombine.

I’ve had so many conversations with friends and colleagues about having a spark of inspiration when I’m on a walk, or in the shower, or in the moments where I’ve just been pottering about, taking some down time to myself. I’m sure you have too.

That’s negative capability in action. It’s taking a minute to ourselves, stopping our irritable reaching after fact and reason, and just being. It helps ignite our imagination and unlocks our creativity.

We live in an attention economy where information is abundant, but our attention is scarce. Platforms and products are engineered to capture and monetise what little head space we have, rewarding immediacy, interruption, and constant novelty – all the conditions that work against the kind of thinking great strategy needs.

It reminds me of a quote from Richard Linklater’s Waking Life, “they say dreaming’s dead, and no one does it anymore”.

Well, negative capability reminds us to take that step back and take that time to dream. To refuse to be nudged toward quick takes or short-term dopamine hits and be taken away from the empty space where better ideas form.

So, breathe. Take a minute. Allow yourself to be bored. Daydream. Let your imagination run wild.

Imagination shows us new futures and possibilities; negative capability steadies us long enough to see those futures clearly and find the strategic unlock that can show us how to bring them to life.

The brands that win won’t be the ones chasing quick answers, but the ones with the courage to hold contradictions until they unlock something truly new.

References

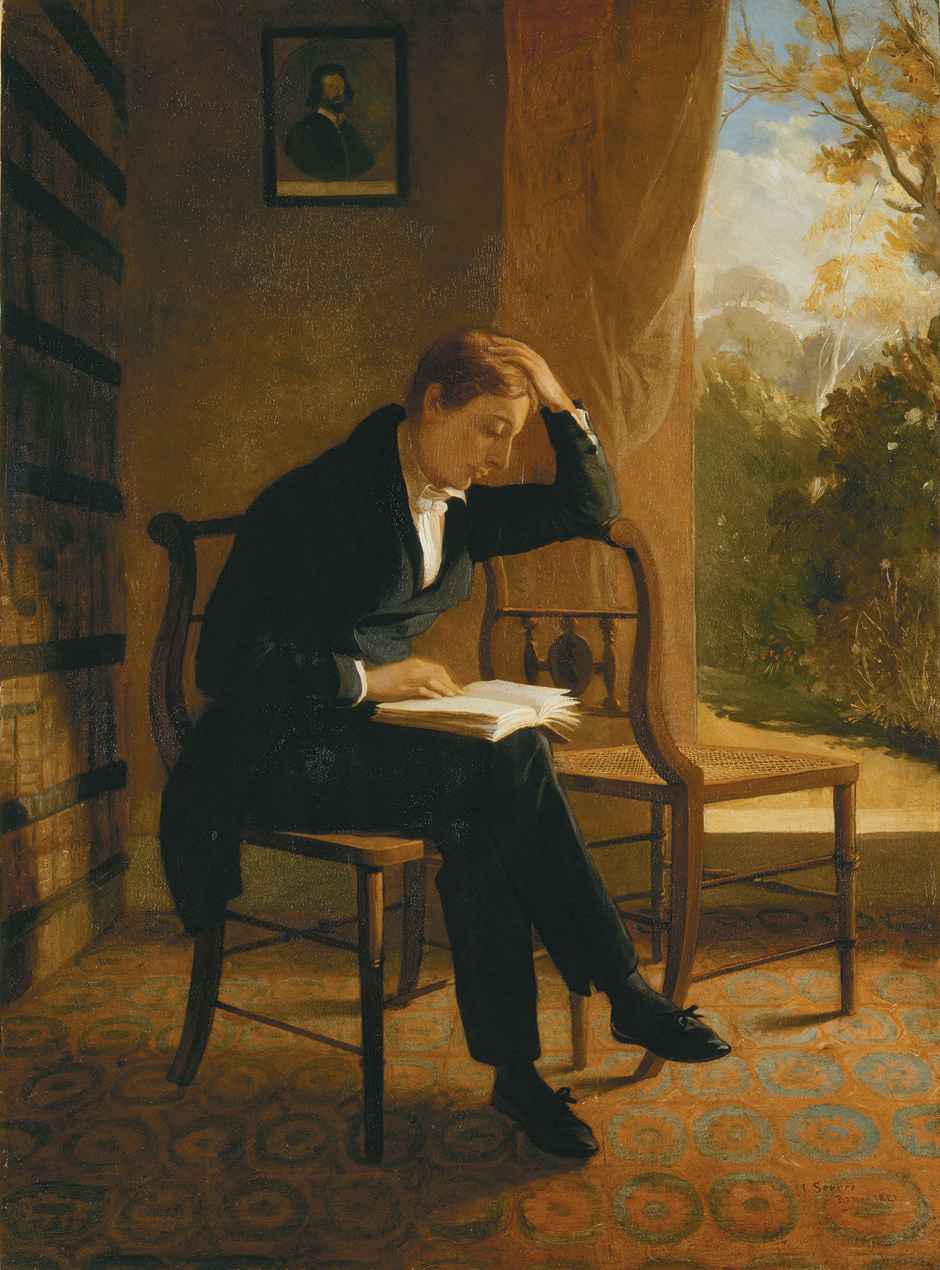

- ‘John Keats’ by Joseph Severn, oil on canvas, 1821-1823, © National Portrait Gallery, London.